THE TRUTH ABOUT HELLO KITTY

Once upon a vinyl coin purse, Hello Kitty captured hearts with her mute, wide-eyed charm. Fast-forward fifty years, and that tiny feline icon, designed by Yuko Shimizu with no grander ambition than selling cute trinkets, has transformed into an $8.5Bn corporate juggernaut. But let’s not be swept away by the saccharine glow of nostalgia or the narrative of inevitable success. The story of Hello Kitty and her parent company, Sanrio, isn’t some fairy tale about enduring charm; it’s a relentless hustle of adaptation, branding genius, and survival tactics. And most recently, at its centre, Tomokuni Tsuji, the 31-year-old CEO, isn’t a magician; he’s a risk-taker who gambled on evolution to drag an ageing empire into relevance.

For years, Hello Kitty was Sanrio’s golden goose. But the goose was limping when Tsuji inherited the family business in 2020. Decades of financial turbulence had left the company bloated on its legacy, struggling to stay afloat in a cultural landscape that had largely moved on. Sure, Hello Kitty was iconic, but icons don’t pay the bills forever, especially when their relevance starts to fade into the background noise of consumer culture.

Sanrio’s brief success streaks, like in 1990’s hyper-kawaii peak and the 40th-anniversary glow-up, were flukes in a broader narrative of stagnation. The truth? Cute alone wasn’t cutting it anymore. Enter Tsuji, whose genius lay not in reinvention but in recognizing the power of diversification.

For a character officially “five apples tall,” Hello Kitty has carried some outsized expectations over the decades. But Tsuji’s masterstroke pulled Sanrio out of her shadow by elevating the supporting cast. In a bold pivot, he championed characters like Aggretsuko, a death-metal-screaming office worker, and Gudetama, a perpetually exhausted egg. These weren’t just adorable faces but avatars of millennial burnout and Gen Z ennui. By leaning into cultural relatability, Tsuji gave Sanrio a shot at connecting with audiences who had outgrown the sugary innocence of Hello Kitty but still wanted to feel seen.

Make no mistake, this wasn’t a sentimental ode to Sanrio’s creative bench. It was calculated. The broader appeal of these characters allowed the company to stay relevant in a market increasingly allergic to one-size-fits-all branding. Cute wasn’t dying; it just needed a jaded twist.

Tsuji also understood that nostalgia thrives on ubiquity. Under his leadership, Sanrio doubled down on strategic collaborations with brands that had nothing to do with kawaii but everything to do with staying visible. Starbucks, the LA Dodgers, and countless other partnerships weren’t about shared values but market penetration.

Meanwhile, Hello Kitty’s TikTok fame, three million followers and counting, was less about a resurgence in organic adoration and more about adapting to the algorithm-driven era. From AI to counterfeiting crackdowns, Tsuji’s team smartly weaponized technology to secure Hello Kitty’s place in the modern world, safeguarding her appeal while steering her into new markets.

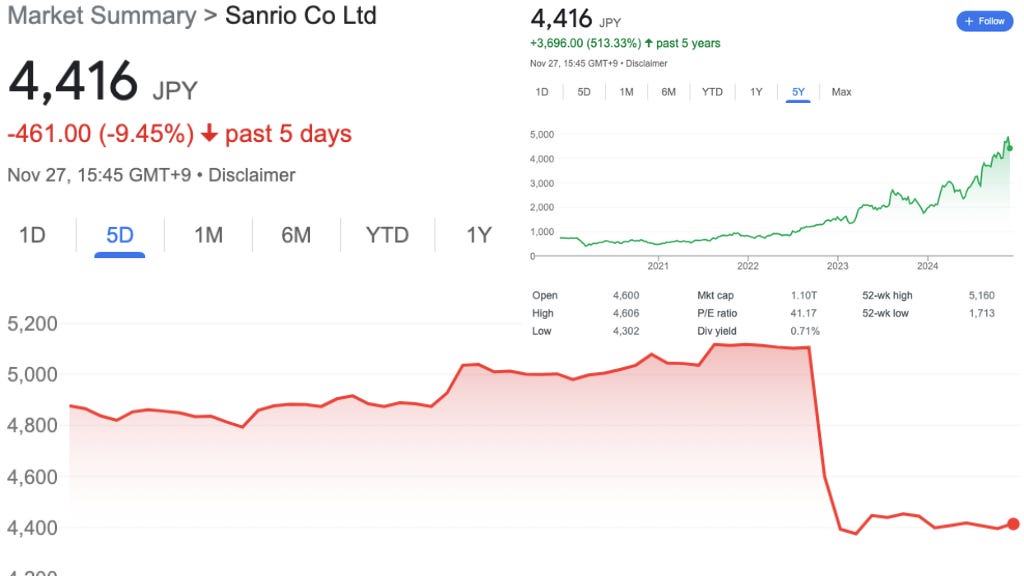

Of course, this transformation hasn’t been without hiccups. Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group's recent sell-off of Sanrio shares, which triggered a 17% drop in the company’s stock price, wasn’t exactly a victory lap. But in the context of Japan’s shifting corporate culture, it wasn’t a death knell either. The move signalled Sanrio’s commitment to shedding its image as a family-run relic and embracing a more globalized, shareholder-friendly future.

In truth, the sell-off was an indictment of old-school Japanese corporate nepotism more than Sanrio’s future. If anything, it might inject fresh perspectives into a company increasingly defined by a single-family dynasty.

Tsuji’s real achievement isn’t in Hello Kitty’s resurgence but in proving that even the most cherished brands need a ruthless willingness to evolve. By blending nostalgia with modern relevance, Sanrio has managed a "V-shaped recovery" that defies Japan’s traditional resistance to change. Under Tsuji, the company has reimagined itself as less of a kawaii monopoly and more of a cultural chameleon.

The cherry blossoms on top are the Warner Bros. Hello Kitty movie, a new theme park in China’s Hainan Island and collabs with almost every household name brand you can imagine. They’re not just evidence of financial viability but the culmination of a strategy combining bold risk-taking with shrewd adaptability.

Hello Kitty’s story isn’t just about a catlike icon thriving for 50 years. It’s about the constant grind of reinvention, the hard truth that even cultural behemoths can’t rest on their laurels. Tomokuni Tsuji didn’t just sprinkle magic dust on a fading legacy; he faced the brutal realities of the modern market head-on and bet on change.

In the end, Hello Kitty isn’t timeless because she’s cute. She’s timeless because she’s never afraid to transform. And that’s the unvarnished truth of why she’s still standing proudly, five apples tall, in a world that’s anything but simple.